When Disarmament Is a Mirage:

Why the Central African Republic’s Peace Accord Was Built to Fracture

Description: A systems-based editorial examining the structural collapse of the Central African Republic’s April 2025 peace accord. Through data-driven insights and institutional analysis, the piece explains why disarmament efforts faltered, how fragile governance undercuts reintegration, and what the quantitative patterns tell us about recurring violence. This editorial integrates findings from a my recent conflict analysis update on CAR and interactive dashboards from data I curated and examined from several key data providers. This full report is available on my projects website: https://data-analyst.mnshakoor.com/projects/central-african-republic/central-african-republic-peace-accord-analysis

The more pressing question in the Central African Republic is not why the April 2025 N’Djamena Accord is unraveling, but why it was considered viable in the first place.

This isn’t a story of bad actors violating good agreements. It’s a story of how peace frameworks, when layered onto fragile or fragmented states, become performative acts, symbolic moments that fail to contend with the actual mechanics of governance, violence, and institutional absence.

To view the full interactive report, quantitative threat dashboard, and analyst commentary, access:

👉 CAR Conflict Analysis Dashboard & Full Report

The System Was the Signal

The N’Djamena Accord was constructed around a familiar disarmament logic: armed groups dissolve, fighters are absorbed into state or civilian structures, and humanitarian frameworks stabilize the transition.

But this logic is premised on two things: that the state has enough reach to administer reintegration and that fighters have enough trust, or desperation, to comply. Neither was true in CAR. The government lacks meaningful authority beyond Bangui. In regions like Ouaka and Ouham-Pendé, governance is more an aspiration than a presence.

The disarmament process, stripped of functioning cantonment zones, food supplies, or vocational programs, left fighters stranded. Ex-combatants in Moyo, Yaloke, and Bokolobo reported no access to basic needs. Some turned to banditry. Others, like the 3R rebels near Nzakoundou, simply regrouped. The reoccupation of Nzakoundou by armed factions on June 28 was not an aberration. It was the most predictable outcome of unmet promises.

Quantifying Collapse: What the Data Shows

From May to July 2025, the highest threat index values emerged in four regions: Ouham-Pendé (236), Haut-Mbomou (238), Vakaga (121), and Haute-Kotto (108). These numbers are not just regional risk markers, they’re institutional audit scores. The regions with the highest instability also happen to be those most neglected by reintegration efforts and security deployments.

Conflict Events (May–July):

Attacks: 213

Armed Clashes: 134

Abductions: 25

Top Hotspots:

Ouham-Pendé (site of 3R resurgence)

Haut-Mbomou (UPC-aligned areas)

Mbomou and Ouaka (zones of incomplete demobilization)

This data, visualized in the interactive dashboard, reflects a simple truth: peace failed not in the abstract, but in the metrics.

A Fragile Accord in a Fragmented State

CAR’s governance architecture lacks feedback mechanisms. Promises are not self-reinforcing. There is no surveillance layer robust enough to detect, deter, and correct noncompliance. The “feedback loop” that political scientists reference, where enforcement failures recalibrate strategies, does not exist here.

Instead, we see what I call elastic ineffectiveness: the system absorbs failure without adaptation.

And this elasticity isn’t benign. It tells armed actors that there’s no cost to remobilization. Worse, it signals to civilians that disarmament is just the prelude to abandonment.

The Identity-Incentive Nexus

The 3R and UPC factions are not simply rogue groups. Their presence in Ouham-Pendé and Mbomou, respectively, is about territorial identity, economic control (roads, mines), and pastoral access. Disarmament, without substituting these functions with institutional alternatives, strips them of purpose but offers nothing in return.

As the ACLED dataset shows, recidivism rates rise in zones where ex-combatants have no access to income, are unsupported by social programs, and are left outside state protection.

This is why violence in CAR should not be read merely as disruption. It is a modality of governance. Armed actors fill the vacuum left by weak institutions, and they do so with greater consistency than peacekeeping deployments or presidential decrees.

Feedback Loops That Spiral, Not Stabilize

The promise to reintegrate 5,000 ex-combatants has been recycled in peace accords since 2017. But DDR (Disarmament, Demobilization, Reintegration) remains an episodic, donor-driven spectacle rather than an institutionalized system. Without biometric tracking, without community-based oversight, without logistical pipelines for food and shelter, DDR is not disarmament. It’s deferred conflict.

The dashboard correlates high threat scores with DDR shortfalls in nearly every region:

Bokolobo, Maloum, Yaloke: Severe supply deficits

Dawala, Thicka, Sataigne: Emerging banditry clusters

Nzakoundou: Site of full rebel reoccupation

The Structural Undercurrent

Look beyond the numbers and a pattern emerges: CAR’s disarmament paradox stems from mismatched incentives. Peace is pitched as mutual de-escalation. But for armed actors, especially in neglected territories, the state offers fewer services than the militias they are asked to abandon.

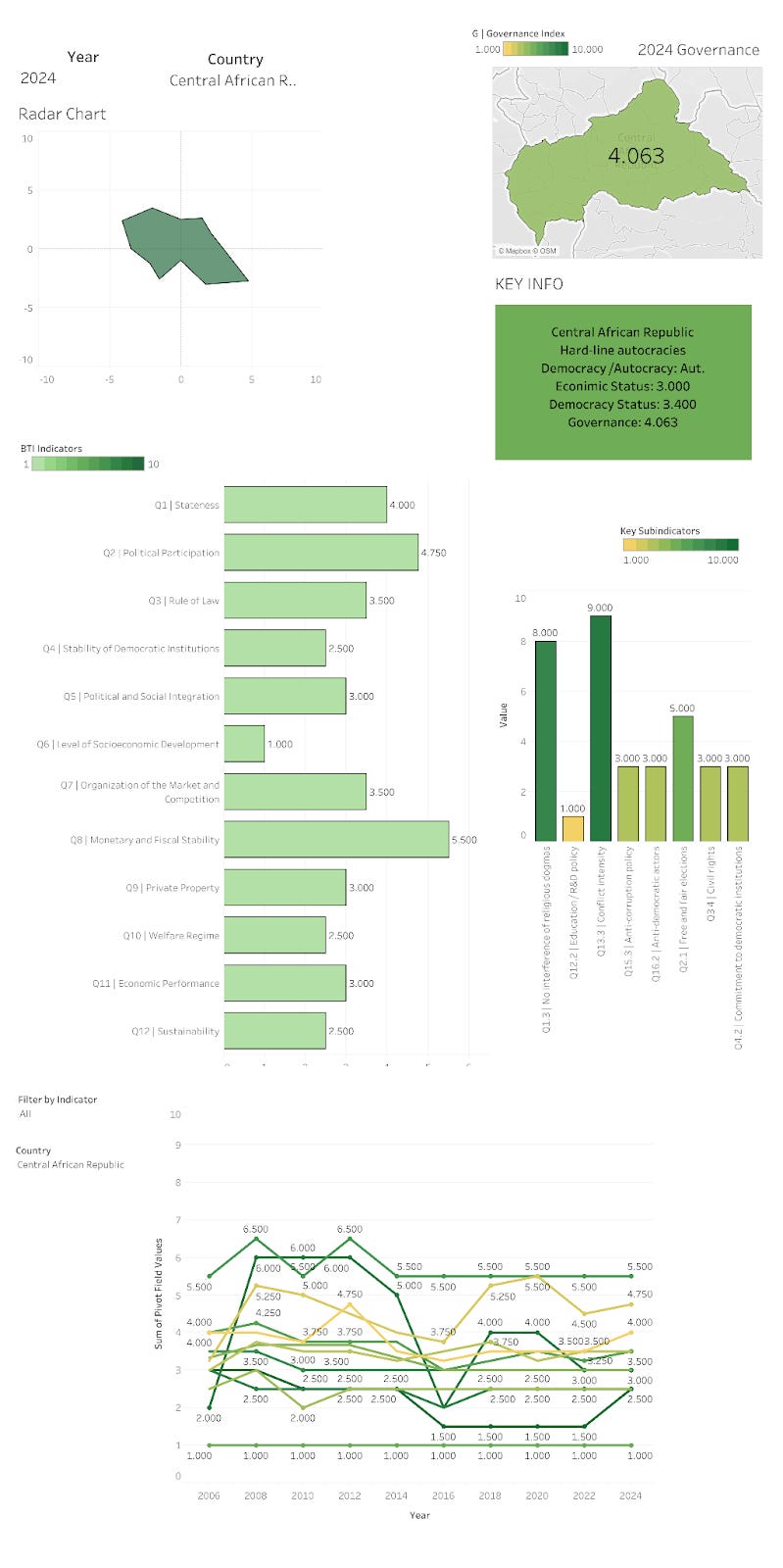

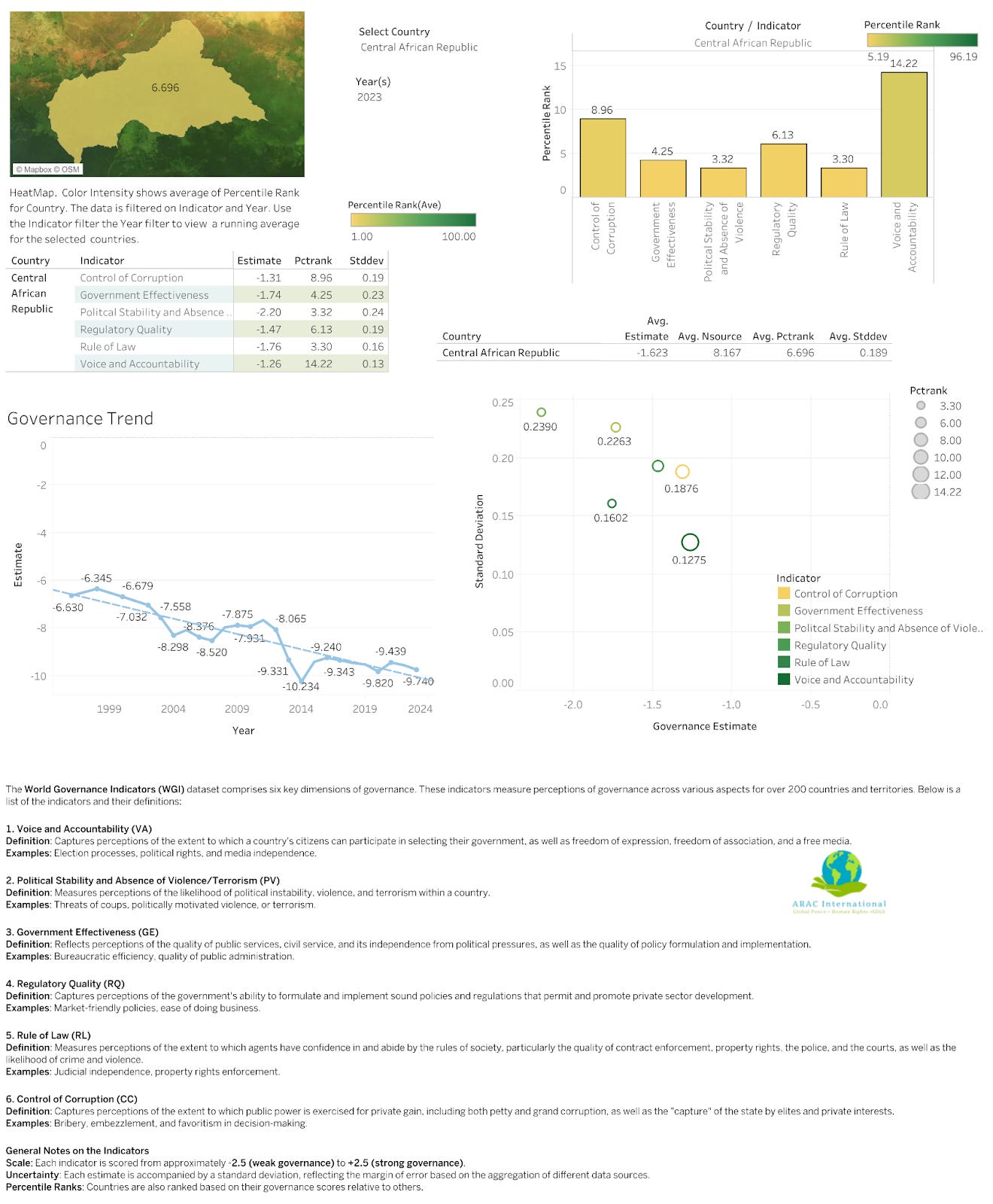

According to the Bertelsmann Index and World Governance Indicators, CAR’s:

Government effectiveness score: -1.74

Political stability: -2.20

Rule of law: -1.76

Classified as the 7th most fragile state globally (FSI)

This institutional fragility is not a backdrop. It is the condition under which every peace agreement must operate. And it shows why each new accord, absent structural reform, resets the clock rather than breaks the cycle.

Toward a Governance-First Approach

What’s missing in most analyses of peace failure is a systemic view. DDR isn’t failing because bad actors broke faith. It’s failing because the system offers no consistent means to track, verify, or support that faith.

Recommendations from the full CAR analysis include:

Deploying biometric and digital voucher systems to trace aid and reintegration

Reinforcing FACA and MINUSCA in threat flashpoints

Establishing cross-border oversight teams with Chad and Cameroon

Creating tiered reintegration plans tied to risk assessments

These are not novel solutions. They are functional basics. But in a system where state capacity is aspirational, even the basics remain unfulfilled.

Final Reflection

The N’Djamena Accord is not unraveling because of betrayal. It’s unraveling because no system was in place to hold it together. The peace was always more narrative than infrastructure.

And until the Central African Republic builds institutional capacity that matches its political promises, every disarmament deal will be an intermission, not a conclusion.

📊 Full Report and Dashboard:

CAR Peace Accord Analysis & Threat Forecast Dashboard

Sources:

World Governance Indicator Dashboard | Central African Republic

Bertelsmann Transformation Index | Central African Repbublic

Soldiers Caught Off Guard Amid Resurgence of Violence in Central African Republic - HumAngle

Violence Resurgence and Disarmament Fragility in CAR Amid N’Djamena Accord

This analysis was produced with support from ARAC’s Peacekeeper Insight, our customized large language model (LLM) research workflow, built on Google (AI Studio & Colab), Mistral & OpenAI GPT architectures, Tableau, and R-Studio. It was developed in-house as part of our Peacekeeper Insight and Digital Navigator Project in partnership with Lladner Business Systems, designed to synthesize open-source intelligence, institutional reports, and regional data into actionable, system-level insights.