Mauritania at a Crossroads

Slavery, Statelessness, and Fragility Exposed | Diaspora Voices, Risk Analysis, and the 8 Pillars of Positive Peace

Recently, I was going through vast amounts of data from the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) and the Varieties of Democracies (V-dem) to set up some analytic dashboard applications before covering this week’s UNGA 80 activities. In the course of aggregating and synthesizing what I had with other global indicators using the analytic AI platform that has been customized and trained for the preferred research process that I use. I currently use several structured analytic techniques (SATs) and risk assessment methods that I use to analyze conflict zones and fragile regions.

Part I. Analyst Commentary: Tandia’s Insights Through the Lens of Positive Peace

While performing my MOS (man on the street) duties for the data journalism portion of my strategic research, I was covering the demonstrations and protests outside the UNGA80 General Debate. During this time, I found myself having a discussion with members of the Mauritanian diaspora who were raising their voices against decades of human rights violations. What began as chants and banners soon turned into testimonies — stories of land dispossession, of families stripped of citizenship, of entire communities displaced across borders since 1989.

Bakary Tandia, a long-time Mauritanian human rights advocate, co-founder of the Abolition Institute, and a leading voice of the diaspora, told me directly, “slavery in Mauritania today we still have” [Diaspora Protesters, 2025]. His words carried the weight of years spent documenting abuses and pushing the international community to confront them. Another beside him added that “our children cannot even go to school without papers, and the state refuses to register us” [Diaspora Protesters, 2025]. These were not abstract grievances; they were explanations of how policy tools like biometric registration have become instruments of exclusion.

Standing in front of the UN’s headquarters, I realized how the Fragile States Index score for Group Grievance was not a statistic confined to a report [Fund for Peace, 2024]. It was in the voices breaking as they described Kaédi, where young activists were killed after the elections [ACLED, 2025]. It was in the anger directed at a government that still shields perpetrators of past atrocities under Law 93-23 [Planning Committee, 2025]. It was in the despair of refugees who, thirty years after deportation, remain in camps across Senegal and Mali [Planning Committee, 2025].

The V-Dem data on democratic stagnation [V-Dem, 2024], the BTI index on weak rule of law [BTI, 2024], and the OSAC warning about protest crackdowns [OSAC, 2024] — all of these indicators were embodied in this small crowd of protestors. They were, in essence, a living dataset. Their signs called for justice, but their presence called for recognition: to be counted, to be acknowledged, to be heard. And in that moment, the conversation became more than fieldwork. It became a reminder that risk assessment is never just about numbers. It is about people who carry the weight of those numbers in their lives every day.

Which is where the analysis must begin. If we take their voices seriously — and we must — the next step is to situate them within the frameworks that help us see structure in what feels like chaos. That means weaving together the governance scores of BTI and V-Dem, the fragility measures of the FSI, the violence data of ACLED, the macroeconomic stressors highlighted by TheGlobalEconomy, and the conceptual scaffolding of Positive Peace. The diaspora’s lived experiences tell us what is broken; the data tells us how deeply. Together, they provide a map of Mauritania’s present fragility and its uncertain future.

1. Well-Functioning Government

Tandia described a state where justice is obstructed by amnesty laws, impunity for perpetrators, and discriminatory administration. This is not merely a governance gap; it is governance against. A well-functioning government is not only about holding elections; it is about whether citizens believe the law applies equally. For Black Mauritanians, Tandia makes clear, the answer is no. The implication: without reform, each act of repression erodes legitimacy and pushes society toward instability.

2. Sound Business Environment

Mauritania’s economy shows headline growth driven by extractives, but Tandia reminds us who is excluded. Statelessness and land dispossession mean that large segments of the population cannot participate in markets or access credit. A sound business environment requires more than foreign direct investment figures; it requires inclusive access to opportunity. If 20 percent of a population lives under servitude-like conditions, markets cannot be efficient , they are distorted by systemic exclusion.

3. Equitable Distribution of Resources

Here Tandia is most forceful. He links land expropriation, denial of citizenship, and exclusion from social benefits as the architecture of inequity. Positive Peace requires that resources are distributed fairly to all groups, not captured by a dominant elite. This inequity is not just moral failure , it is a strategic vulnerability. Grievances accumulate, feeding the very instability Mauritania claims to be immune from.

4. Acceptance of the Rights of Others

This is perhaps the core of Tandia’s testimony. He insists that despite abolition laws, Black Mauritanians remain denied dignity, citizenship, and recognition. Acceptance of rights is not about rhetorical commitments; it is about whether minorities can live without fear of repression or erasure. Tandia’s diaspora activism is itself proof of the deficit. If rights were secure, there would be no need for exile advocacy at the UN General Assembly.

5. Good Relations with Neighbors

Tandia situates the crisis not just within Mauritania’s borders but across Senegal and Mali, where tens of thousands of refugees still languish. Good relations with neighbors cannot rest solely on counterterrorism coordination. They require restitution, refugee return, and cross-border reconciliation. Positive Peace means regional relationships built on shared security and shared dignity, not one-sided expulsions.

6. Free Flow of Information

He emphasized how repression silences voices at home, making the diaspora the custodian of memory and truth. A society where citizens risk arrest for peaceful assembly or speech is one where information cannot flow freely. Tandia shows that in such conditions, information migrates , it lives in exile. But this is not sustainable. Free flow of information inside Mauritania is essential to build trust and reduce misinformation-driven polarization.

7. High Levels of Human Capital

Statelessness denies thousands of children access to education. Land dispossession reduces the ability of families to invest in health or skills. Human capital is not a technocratic measure , it is the lived accumulation of education, health, and dignity. Tandia’s point is that systemic exclusion squanders human potential at scale. In demographic terms, with 60 percent of Mauritanians under 25, this is a crisis hiding in plain sight.

8. Low Levels of Corruption

Finally, Tandia pointed to how perpetrators of past atrocities are not only shielded but promoted. This is the definition of corruption in Positive Peace terms: when public office becomes an instrument of impunity rather than accountability. Corruption is not only theft of resources but theft of justice. As Tandia stresses, a state that rewards those who repress cannot credibly claim stability.

What emerges from viewing Tandia’s testimony through the 8 Pillars is a paradox: Mauritania scores high on external stability because it suppresses instability internally. But Positive Peace reminds us that stability without justice is brittle. Each pillar reveals an inverted architecture. Governance functions to repress, not serve. Resources flow unevenly. Rights are denied. Information migrates abroad. Human capital is squandered. Corruption is normalized.

The lesson here is that stability cannot be measured by the absence of war alone. It must be measured by the presence of justice, equity, and dignity. Tandia is not just recounting abuses. He is mapping out the absence of Positive Peace. His testimony, in effect, provides a diagnosis a reminder that Mauritania’s “peace” is negative peace, sustained by repression, and that without structural change, fragility will deepen.

Part 2. Situation Report

Country Focus: Mauritania

Date: 16 October 2025

1. Executive Summary

This report provides a strategic overview of Mauritania’s sociopolitical risk environment, incorporating media sentiment analysis, predictive scenario modeling, longitudinal governance indicators, and narrative discourse mapping. The analysis reveals a fragmented reform landscape characterized by cosmetic policy adjustments, entrenched identity divisions, and an increasingly dual-track narrative between state-aligned optimism and civil society’s structural criticism.

Strategic Implication: Mauritania is exhibiting signs of chronic institutional stagnation. While external actors may recognize superficial progress, underlying conditions remain volatile — especially concerning civic freedom, legal impartiality, and social stratification.

2. Event and Narrative Summary (2023–2025)

Key Events Identified via GDELT (2023–2025):

Recurrent international human rights reporting (e.g., U.S. State Dept., Human Rights Watch).

Government responses challenging external critiques (e.g., rejection of HRW reports).

Coverage of Haratine identity debates indicating unresolved social fractures.

Instances of repression or tension between the state and civil society actors.

These headlines were dominated by linguistic dichotomies: progress vs. denial, identity vs. legality, and freedom vs. state control.

3. Structured Analytic Findings

a. ACH (Analysis of Competing Hypotheses):

Most Probable Explanation:

Mauritania’s reforms are selective and externally motivated, with deep informal structures of exclusion and repression still intact.

Evidence supporting progress comes primarily from government-aligned or international diplomatic sources.

Contradictory evidence from activists and independent press points to enduring human rights issues.

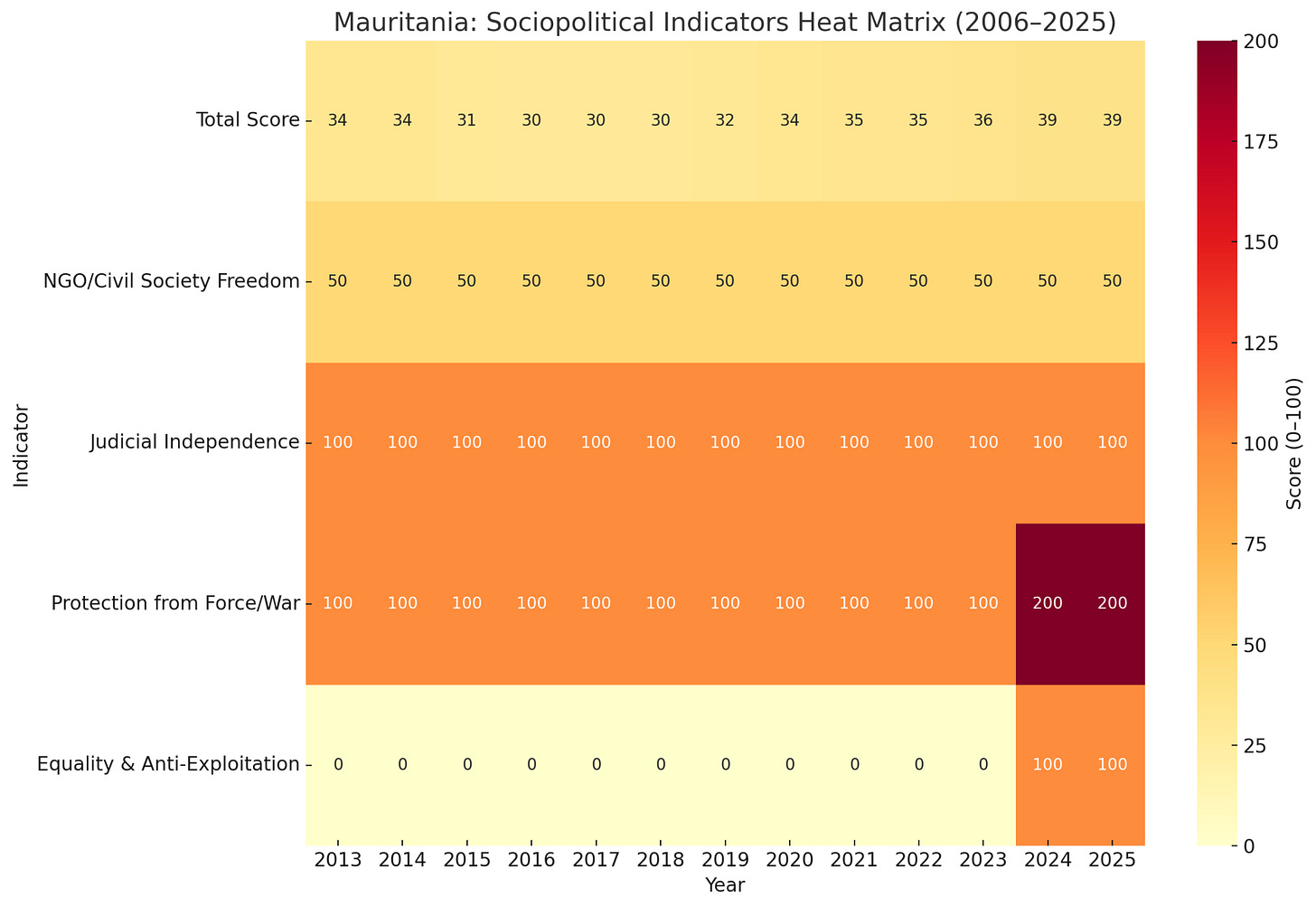

4. Longitudinal Institutional Assessment (FIW Indicators 2006–2025)

Freedom Score (2025): 39/100 → Partly Free

Civic Space & Equality: Static or degraded since 2010; civil society remains institutionally weak.

Judicial Independence & Physical Security: Consistently low; no systemic improvement.

Tiered Watchlist Alert:

Mauritania qualifies for Tier 2 on the IGRIS Alert System:

“Entrenched elite consolidation and suppression of civic expression, with long-term exclusion risks escalating if triggered by crisis (e.g., external shock, elite fragmentation, or regional contagion).”

5. Cognitive Linguistics Analysis of Domestic Discourse

Frame Conflicts Observed:

Legitimacy Frame: State discourse portrays reforms as sovereign and orderly. Counter-discourse frames the state as illegitimate and selectively reformist.

Moral Voice Conflict: Activists position themselves as custodians of “conscience” while the government asserts monopoly over national truth (e.g., “أنتم لستم مديرين للضمير الوطني”).

Ontological Insecurity: Headlines probing “Who are we?” or debating Haratin identity reflect an unsettled national narrative — indicating that citizenship and belonging remain contested constructs.

Narrative Structures:

Activist headlines use alarmist urgency (“انتهاكات”، “الاعتقال”، “القمع”).

Government rebuttals often use delegitimizing metaphors (“تقرير يفتقر للموضوعية”).

The linguistic field shows parallel realities between internal perception and international portrayal.

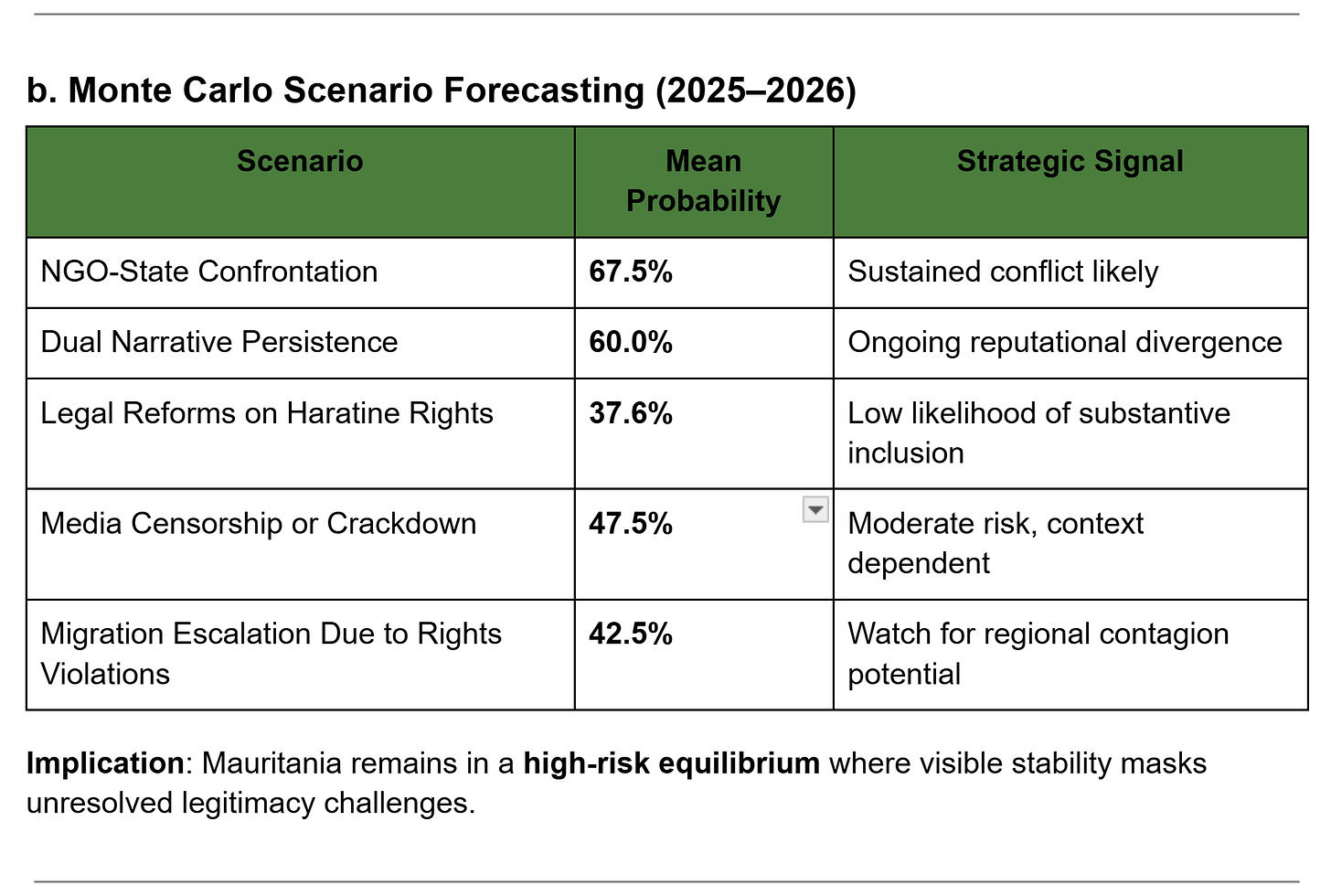

6. Predictive Assessment

Short-Term Outlook (3–6 months):

Political stasis will likely continue unless externally disrupted (e.g., donor leverage or domestic scandal).

Further confrontations with NGOs and press are probable.

Medium-Term (6–12 months):

Legal gestures (e.g., symbolic reform) may be made to maintain donor relations.

Structural transformation unlikely without elite turnover or mobilization of excluded populations.

Long-Term (12–24 months):

If trends persist, Mauritania risks entrenching into hybrid authoritarianism, with periodic liberal signals masking systemic exclusion.

7. Recommendations

For International Actors (Donors, INGOs, Diplomats):

Shift from outcome-based to process-based benchmarks (e.g., judicial transparency, participatory inclusion).

Condition legitimacy and funding on civic space metrics, not just security cooperation.

Support local epistemic actors (activist scholars, community journalists) to enrich the domestic discourse landscape.

For Regional Risk Monitors:

Establish an Early Warning Indicator Matrix, integrating:

Sudden increases in anti-NGO rhetoric

Drop in Haratine representation in civic bodies

Disinformation bursts around “sovereignty” or “foreign agendas”

For Internal Reform Advocates:

Continue developing a narrative framework grounded in national ethics rather than Western liberalism alone.

Leverage diaspora media networks to amplify cognitive counter-frames.

8. Datasets

Data Sources:

GDELT Structured Headlines Dataset (2023–2025) curated by MNS Consulting

Freedom in the World Subcategory Dataset (2025)

ACLED/V-Dem/BTI (referenced indirectly) curated by MNS Consulting

PESTELS + Demographic Analysis by ARAC International Inc.

Structured Analytic Techniques Framework

Methodologies Used:

Structured Analysis (ACH, Hypothesis Testing, CARVER, Scenario Mapping)

Cognitive Frame Analysis (Frame Semantics, Ontological Security Theory)

Monte Carlo Probabilistic Forecasting (10,000 simulations)

IGRIS (Integrated Geo-Risk Intel System) MNS Consulting standard research procedure which consists of the 3 aforementioned components

Historical Risk Trend Evaluation (FIW Time Series)

Source: Shakoor, M. N. (n.d.). Interactive PESTELS Analysis: Mauritania. Quanta Analytica. https://quanta-analytica.mnshakoor.com/reports/mauritania/

TheGlobalEconomy.com. (n.d.). Mauritania. Retrieved October 2, 2025, from https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Mauritania/

Bertelsmann Stiftung. (2024). Mauritania country dashboard. In Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) 2024. https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-dashboard/MRT

Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. (n.d.). Country graph. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute. https://v-dem.net/data_analysis/CountryGraph/

U.S. Department of State. (2024). Mauritania: 2024 trafficking in persons report. Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons. https://www.state.gov/reports/2024-trafficking-in-persons-report/mauritania/

Overseas Security Advisory Council. (2025, September). Mauritania: Crime and safety report. U.S. Department of State. https://www.osac.gov/Content/Report/52a21730-0aea-4390-b723-284f365c90ad

Mauritania. (2007, September 3). Loi n° 2007-048 du 3 septembre 2007 portant incrimination de l’esclavage et des pratiques esclavagistes [Law No. 2007-048 of 3 September 2007 criminalizing slavery and slavery-like practices]. International Labour Organization (ILO), NATLEX. https://natlex.ilo.org/dyn/natlex2/natlex2/files/download/111719/MRT-111719.pdf

Shakoor, M. N. (2025). QA-GDELT Explorer. Retrieved October 16, 2025, from https://mnshakoor.github.io/qa-gdelt-explorer/